To explain how the Georgia election was supposedly stolen for President Joe Biden in 2020, former President Donald Trump described the hypothetical sabotage of the voting system simplistically. “With the turn of a dial or the change of a chip, you can press a button for Trump, and it goes to Biden,” Trump said in a December 2020 speech.

But there are no dials on the Dominion Voting Systems machines used statewide, suggesting that, like most of the electorate, Trump seems to know little about what happens to a vote once it’s cast in Georgia. The counting, certification, and auditing stages of an election are a black box for most Americans.

Atlanta Civic Circle recently got a behind-the-scenes look at how the Dominion voting system works in Georgia through a tour from the Cobb County Election Office—courtesy of Michael D’Itri, who has run ten elections as Cobb’s preparation center division manager. Here are some key takeaways from our tour:

There’s no app for that

The touchscreen machine that voters use to make their choices—called a “ballot-marking device” (BMD)—looks like an iPad. But that doesn’t mean these devices operate like apps or that votes are directly uploaded to the cloud to be counted. The Dominion machines are not connected to the internet, and there’s a lengthy paper trail of records at multiple stages of the process.

After someone votes, the voting data from each memory card is inputted into Election Management System (EMS) computers, which aren’t networked. The first time the precinct data are subject to an internet connection is during the next stage, when the results are transported to a secure server room at the county’s election headquarters and uploaded to the Secretary of State’s portal, which the news media can access.

After the polls close at 7 p.m. on Election Day, poll workers at each precinct generate three printed copies of tabulation results from the memory cards, known as “tabulator tapes.” The tapes list the number of ballots processed, the number of votes received for each candidate, and write-in votes for the precinct.

The signed tabulator tapes are then attached to an official statement of results for the precinct. “That’s huge on the evidence side, because it has a direct relation to what was cast in the machine and what is on those memory cards. That tape should match the report placed on the computer,” said D’Itri.

Security is everywhere

Georgia’s electronic voting machine system is currently the subject of a long running federal lawsuit brought by an election integrity nonprofit in 2017. The plaintiffs want the state to scrap the voting machines, which they argue are vulnerable to hacking, and have voters hand mark paper ballots instead, as nearly 70% of voters do elsewhere in the country. An almost three-week bench trial concluded Feb. 1, and now the case awaits a ruling from U.S. Northern District of Georgia Judge Amy Totenberg.

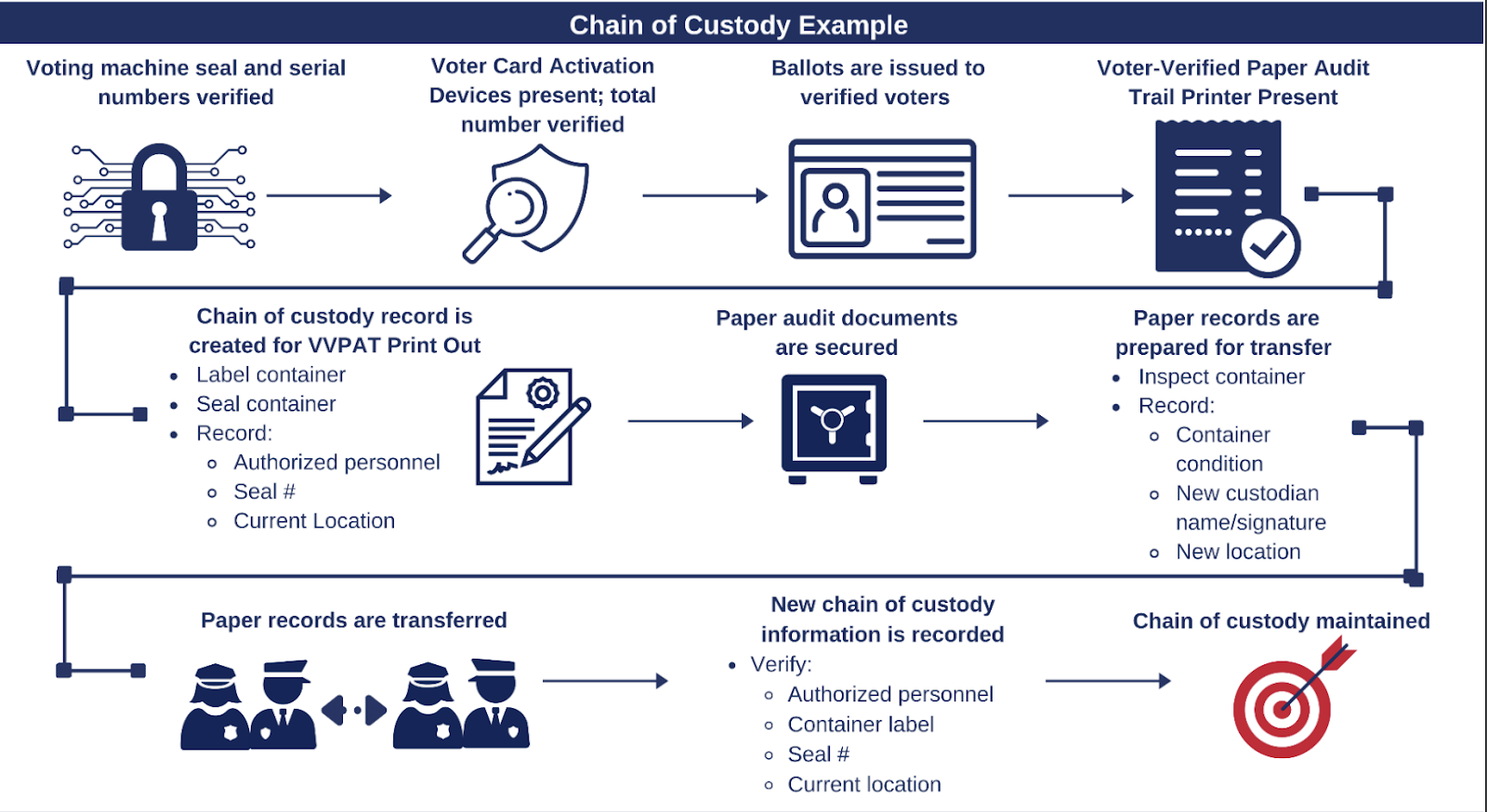

But to hack Georgia’s elections in person, one must bypass a host of security measures and a county’s elaborate chain of custody process. The U.S. Election Assistance Commission describes the chain of custody as the “process, or paper trail, that documents the transfer of materials from one person (or place) to the next.”

Cobb County’s voting machines are stored in the warehouse section of their Marietta office. All of the machines, other voting equipment, and materials are logged, inventoried. The machines themselves are sealed with five or six tags, each bearing unique serial numbers. When an election official opens a ballot container, a new seal is attached, and the serial number is recorded.

When polls close, election workers similarly have to follow a detailed list of instructions on placing paper records and memory cards into colored bags, which are also sealed, all under the observation of multiple officials. Each vehicle hauling voting materials to Cobb’s election headquarters from the county’s over 140 polling places also must have two workers, and their car trip is timed to arrive promptly.

Additionally, election observers and a surveillance system monitor all vote handling and machines. “This stuff is recorded 24/7, and I got cameras’ eyes in the sky everywhere. I can see who, and this area in particular is secure,” said D’Itri, referring to Cobb’s election headquarters. “I’m not a hacker. But what I can say is that the procedures that we put in place severely mitigate somebody’s ability to come in and cause fraud during an election.”

Testing, testing

For Cobb’s elections office, which is one of the largest in the state, preparation occurs nearly all year round, but typically ramps up two months before an election day. The office hires and trains about 1,000 temporary election workers for a smaller election, such as this month’s presidential primary, and more—two to three thousand—for the big Nov. 5 General Election.

Each piece of equipment is tested beforehand to make sure it functions correctly. The touchscreen machines that voters use to make selections are inspected for dead spots, and printers are checked to ensure there are no QR code smudges when ballots are printed.

For instance, during Cobb’s final stress test before the March 12 primary, the batteries that powered election machines passed inspection 97.9% of the time. That meant 41 needed fixing or replacing. The biggest issue? Finicky ballot scanners. “Sometimes we have optical scanners that might be a little dirty with ink or dust and just need a good cleaning,” said D’Itri.

Once poll workers are trained and all of the voting equipment has been vetted, Cobb County conducts a big stress test—a dress rehearsal of sorts for the election. Election officials draw on past voter turnout data to run a commensurate number of test votes on the system.

The whole testing process takes a total of about five weeks, but it’s an intensive period that includes hundreds of hands-on hours. D’Itri says his team has worked as many as 47 days without a day off while preparing for an election. Thus, if Election Day is democracy’s equivalent of the Super Bowl, county election officials must endure a long regular season to get there.

Want to see it work for yourself?

The Cobb County Election Office encourages ordinary voters to get their own tour. Here’s how to reach them:

Email: electionsinfo@cobbcounty.org

Phone: (770) 528-2581

Address: 995 Roswell St. NE, Marietta, GA 30060

More propaganda to protect machines that miscounted most notably in DeKalb county in May 2022 and have been proven to contain the Williamson Error in 97% of Georgia counties.

Our ballots are not even secret- they are mailed with USPostal Service bulk mail and not one county track delivery to assure the ballot arrived to the intended recipient.

See the truth at http://www.GaBallots.com

More propaganda to protect machines that miscounted most notably in DeKalb county in May 2022 and have been proven to contain the Williamson Error in 97% of Georgia counties.

Our ballots are not even secure- they are mailed with USPostal Service bulk mail and not one county track delivery to assure the ballot arrived to the intended recipient.

See the truth at http://www.GaBallots.com