Last month, Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp attended a fundraising luncheon for his political action committee with First Lady Marty Kemp at a major Atlanta law firm. The keynote speaker was Justice Andrew Pinson, whom Kemp appointed to the Georgia Supreme Court in 2022 from the Court of Appeals.

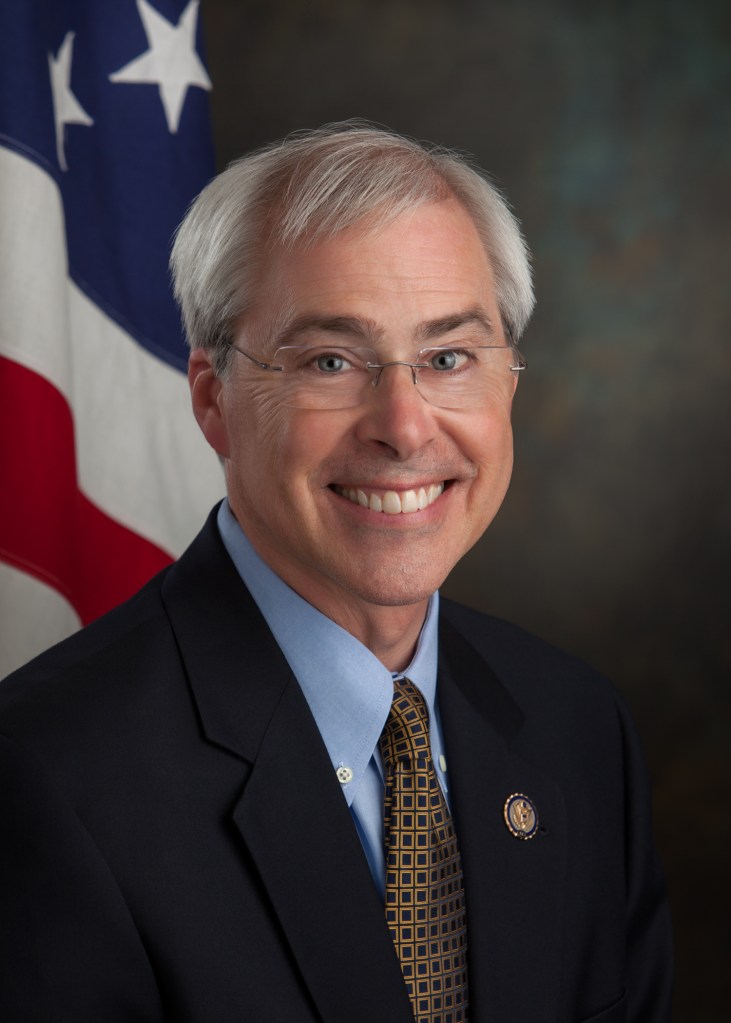

In the first seriously contested Supreme Court race in decades, Pinson is facing a high-profile, well-funded challenger, former Democratic Congressman John Barrow, to keep his seat. The fundraiser for Kemp’s Georgians First Leadership Committee at Troutman Pepper had a suggested donation amount of $2,500 per person.

That was one of many signs that the Pinson-Barrow contest is one of the most competitive and expensive Supreme Court races Georgia has seen in years. It’s also testing the norms of campaign speech for judicial candidates — reflecting the reality that even non-partisan races are not immune from partisan politics.

Ordinarily, incumbent judges run unopposed, but Pinson has attracted a challenger, Barrow — and the former Athens Congressman is making abortion rights a centerpiece of his campaign for the May 21 election.

Fundraising and free speech

That a Republican governor is fundraising with a candidate for a nonpartisan judicial seat may seem unusual, but it’s perfectly legitimate. There are no rules that prohibit elected officials in Georgia from offering political support, money or endorsements to nonpartisan candidates — including judges.

“It’s completely and totally normal,” said Marc Hershovitz, an elections law attorney who managed former Georgia Supreme Court Justice Robert Benham’s successful 2002 re-election campaign.

Just last week, Kemp appeared alongside former Democratic governor Roy Barnes at a fundraiser for Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee, who is overseeing the sprawling election racketeering case against former President Donald Trump. McAfee has also attracted a challenger for his seat.

Instead, what has ruffled feathers in the legal community — and drawn a complaint from the Georgia Judicial Qualifications Commission (JQC) — is that Barrow is making the fight over abortion access a central theme of his campaign. In his speeches and ads, he’s staked out the position that abortion rights are protected by Georgia’s constitution.

Since ongoing legal challenges to Georgia’s six-week abortion ban will likely go to the state Supreme Court, Barrow has been criticized for signaling how he would rule in advance. The JQC’s complaint said Barrow must bring his campaign speech and ads in compliance with state judicial ethics rules that bar judicial candidates from raising doubts about their impartiality by saying how they would rule.

“This idea that you didn’t talk about issues that were going to come before that court was just something everybody agreed on, and that seems to have gone out the window this time — which really is kind of a new situation, I think, for everybody,” said Bryan Tyson, an Atlanta election lawyer who supports Pinson.

In response to the JQC complaint, Barrow on May 6 filed a federal lawsuit accusing the JQC of violating his First Amendment rights by attempting to censor his campaign speech.

Partisan politics or par for the course?

Asked about the law firm fundraiser and Kemp’s support for Pinson, Kemp’s Georgians First Leadership Committee PAC provided a statement from the governor to Atlanta Civic Circle.

“Justice Pinson has served our state with dignity and respect on our state’s highest court,” it said in part. “His opponent is a career politician who is more focused on running a campaign based on partisan politics and division than he is about upholding the rule of law and serving Georgians with honesty and integrity.”

“We need to keep conservative voices like Justice Pinson on the bench who follow the Constitution, and [First Lady] Marty and I are committed to doing all we can to support him in his upcoming election on May 21,” Kemp added in the statement.

Pinson’s campaign did not respond to emailed questions. Pinson also declined to participate in the Atlanta Press Club’s Loudermilk-Young debate against Barrow in late April, leaving Barrow to debate an empty podium.

The Georgia Supreme Court justice told the Atlanta Civic Circle in a response to the 2024 May primary voter guide that it would be inappropriate for a judge, who is supposed to be nonpartisan, to opine on issues before they come before the court.

“We have resisted judicial activism in Georgia. I am committed to keeping it that way, and I am hopeful that how I serve as a judge will show the public judges can apply the law impartially and not play politics.”

But Barrow — who has attacked Pinson on the abortion issue and won an endorsement from the group Reproductive Freedom for All — has a different point of view on what “non-partisan” means. “Partiality has nothing to do with your opinions about the law,” he said at the debate. “It means you’re not going to favor one party [in a case] over another.”

As for Pinson’s comment that prospective judges shouldn’t comment on political issues, Barrow said, “That’s not true and he knows it. The Georgia Code of Judicial Conduct specifically states that it does not prohibit a judge from stating his views on a disputed issue.”

Free speech v. judicial conduct code

Hershovitz agrees with Barrow’s interpretation. “If you’re going to have an election, you have to allow the candidates to talk about abortion,” he said. “When you say nonpartisan, you’re just saying not Democrat or Republican. You’re not saying that there aren’t issues.”

But for Tyson, Barrow’s break with judicial campaign norms is less about whether he’s violating Georgia’s Judicial Code of Conduct, or whether that code violates the U.S. Constitution as Barrow contends in his lawsuit, and more about what precedent he may be setting for future judicial contests.

“I think it’s going down a very dangerous path of people running as, basically, politicians for offices on the state Supreme Court, which has very important roles in defining the law and legal issues that affect everybody,” Tyson said.

The issue with Barrow, Tyson continued, is that the Supreme Court candidate is “prejudging” by stating on the campaign trail that a woman’s right to choose an abortion is enshrined in Georgia’s constitution. “If you bring me a case that asks ‘Is there a right to choose in the Georgia constitution?’ I’ve already told you how I’m gonna rule. That’s the problem,” he said.

“The reality is what he’s saying would apply to every [judicial] election all the way down,” Tyson said. ”Again, even if he’s right, as a matter of law, we’ve been able to do this in Georgia for a long time without running into issues.”

“I see a distinction between what is wise policy and what is required by law,” he added.

That question was at the core of a 2002 U.S. Supreme Court case — Republican Party of Minnesota v. White — in which the court ruled 5-4 that Minnesota’s restriction on judicial candidates from opining on disputed legal or political issues was unconstitutional.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who voted with the majority, later said the Supreme Court decision gave her pause. In a concurring opinion, she raised the broader concern that judicial elections in general undermine the aim of having an impartial judiciary in the first place.

“Elected judges cannot help being aware that if the public is not satisfied with the outcome of a particular case, it could hurt their reelection prospects,” O’Connor wrote. The Supreme Court justice added that campaign donations could also make judges feel beholden to donors.

Big money for a judicial race

Pinson has far outraised and outspent Barrow for the state Supreme Court seat, according to financial disclosures from the first week of May. Pinson had raised over $1.3 million and spent just shy of $600,000 as of May 6. Barrow had raised just under $806,000 and spent over $531,000 as of May 3.

Election observers agree that this is big money for a judicial race. “$700,000 is a lot of money to have raised for a judicial campaign because people just aren’t that interested [usually],” Hershovtiz said. “This is a seriously contested race.”

Learn more about Barrow, Pinson, and other candidates on your primary guide. Build your ballot at Georgia Decides, brought to you by Atlanta Civic Circle and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

I’m at a point where if I see a “R” by a candidate’s name or other people with “R”s by their names on a ballot endorse the person, I’m voting for the other person or the person with the “D” by their name. The Republican Party has had a 20+ stranglehold over the state of Georgia. It’s not even a democracy much less a republic in Georgia. It’s a religious oligarchy.

While big money may raise some eyebrows, judicial campaigns like these in Georgia are always going to get large contributions from the legal community – individual attorneys as well as firms. It’s not a shock that a law firm hosted Pinson.