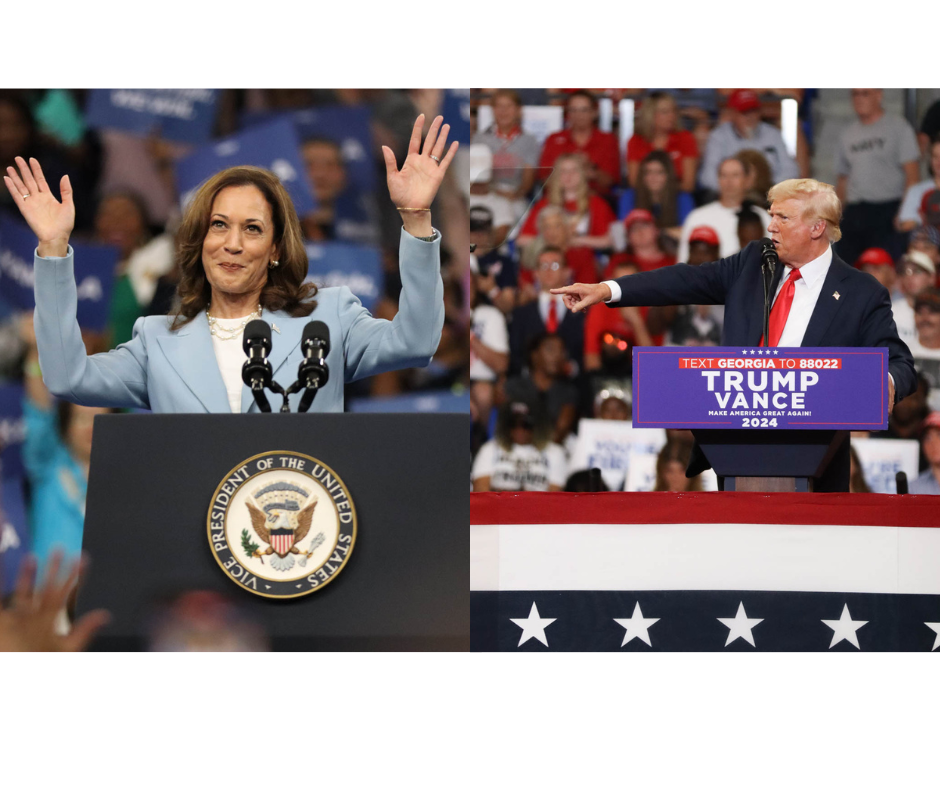

During a campaign stop in Atlanta last month, Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential contender, vowed that, if elected, her administration would “take on corporate landlords and cap unfair rent increases.”

Likewise, U.S. Sen. J.D. Vance, the Ohio Republican vying for the vice presidency on Donald Trump’s ticket, has lamented institutional investors’ outsize influence on housing markets nationwide. During his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, he said: “Wall Street barons crashed the economy, and American builders went out of business.”

Former President Trump, too, has pledged to lower housing costs and reduce homelessness in his Agenda 47 platform: “To help new home buyers, Republicans will reduce mortgage rates by slashing inflation, open limited portions of federal lands to allow for new home construction, promote homeownership through tax incentives and support for first-time buyers, and cut unnecessary regulations that raise housing costs,” his campaign’s policy document says.

But how does the highest office in the country actually fulfill such promises? It goes beyond urging Congress to pass legislation or appointing a boss to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), according to one White House housing policy insider.

Tia Boatman Patterson, the Biden administration’s former associate director of housing, treasury, and commerce in the Office of Management and Budget — and a longtime leader of housing development agencies in California — said each president has at their disposal an array of levers to pull to shape housing policy.

First and foremost, of course, “The president has the bully pulpit” — vast influence over how officials from Capitol Hill to city halls discuss and address policy issues — she told Atlanta Civic Circle in an interview.

But the commander in chief also wields the ability to appoint literally anyone to myriad federal offices that determine how housing is built, funded, maintained, and inspected, not to mention how developers and landlords are regulated.

“The president does appoint the HUD secretary, which helps implement housing policy,” said Boatman Patterson, who now leads the California Community Reinvestment Corporation, a housing finance nonprofit. “But the president also appoints the FHFA director.”

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) is an independent authority that regulates and oversees government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), such as the mortgage lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as well as the 11 banks of the Federal Home Loan Bank system.

“Those GSEs were established to provide liquidity in the housing market, and they’re there to support affordable housing and community development,” Boatman Patterson said. “So by appointing that [FHFA head], who has a belief that that system is supporting affordable housing and community development, that helps lead those policy conversations.”

“So it’s not just legislation,” she continued. “It’s regulatory as well.”

How housing gets politicized

Boatman Patterson insists that housing policy “should be completely nonpartisan” — but she recognizes that’s typically not the case.

For instance, the Biden administration and the Harris campaign have argued that homelessness issues are best tackled with a “housing-first” approach — the idea of getting people housed first and then addressing other needs around mental health, addiction, and employment. But the Trump camp has pushed a “treatment-first” model, which revolves around the idea that people must get sober and get jobs before they can receive any federal housing benefits.

“It’s not an either-or,” Boatman Patterson said. “I think that by pitching it as an either-or, that’s where we miss opportunities. There are some folks who simultaneously need treatment and housing and some folks whom you can [just provide] housing” to enable self-sufficiency.

The president also has near unilateral power to decide how housing subsidy programs operate by appointing the people to the federal agencies overseeing them.

Boatman Patterson cited a specific example from her time as the director of California’s Housing Finance Agency, when Trump was president: The Republican administration rolled back an Obama-era program that had for years provided financial assistance to first-time homebuyers who were making up to 150% of the area median income (AMI) in areas where housing was increasingly expensive.

The overhauled program made it so that people at that income level — middle-class buyers — could no longer reap those benefits; it instead focused on people earning 80% AMI or below. “So they only wanted to help low- or extremely low-income homeowners,” she said, noting that an entire economic class struggling to achieve the American Dream of homeownership was deprived of such assistance.

That didn’t take legislation; it simply required the president to instruct political appointees to do away with the Obama administration’s policies. And that’s not uncommon, for any presidency.

Federal agencies aplenty

In addition to filling leadership positions at HUD and the FHFA, the president places people in power at the U.S. Treasury and Justice Departments, which both control housing-related programs and regulations.

The Treasury Department, for instance, disburses rental assistance, and the Department of Justice enforces fair housing laws, according to the Revolving Door Project, a government watchdog organization.

Biden’s Justice Department recently announced it was mounting a major lawsuit against institutional landlords and other companies accused of price-gouging in the housing market — an effort that, if Vance is to be believed about his campaign concerns, could continue should Trump win the November election.

What’s more, the Departments of Agriculture and Veterans Affairs, along with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, each run housing assistance programs for very specific demographics — people living in underserved rural communities, military veterans, and those impacted by natural disasters, respectively.

And then there’s the Department of the Interior, which runs the Housing Improvement Program for Native Americans.

“[Presidents] also have the ability to lean in on regulatory reform and other things that can make it easier toward production and housing supply,” Boatman Patterson said, referring to how federal agencies allocate housing production funding to states, counties, and cities, “and to provide incentives so that states would become PRO Housing jurisdictions and can incentivize their local governments to remove regulatory barriers.”

Although the federal budget requires Congressional approval, the president also has a tremendous amount of influence over federal funding for each of these many agencies.

But why should average Americans care about the presidential candidates’ housing policy platforms?

“Housing cost is the biggest contributor to inflation,” Boatman Patterson said. “It is touching every jurisdiction in the United States. It used to be that just a few people would worry about it — but now, you have kids who are coming home from college and they have no place that they can rent in their own neighborhood, they have no place they can buy in their own neighborhood, because they’ve been priced out.”

“Everyone should be concerned about this,” she added.