Editor’s note: Atlanta Civic Circle pursued this story after multiple Atlanta City Council members raised concerns that the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund wasn’t being used as intended. Mayor Andre Dickens’ office supplied a 4,159-row spreadsheet of all the fund’s transactions since its inception in late 2021, which we have analyzed for our readers.

The city of Atlanta’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund, formed to bankroll affordable housing initiatives, is now being used to cover housing bond debt and staff salaries — a shift that’s alarmed housing advocates and several city officials.

The Atlanta City Council created the trust fund in late 2021 “to ensure adequate annual funding for affordable housing initiatives.” But for fiscal year 2025, Mayor Andre Dickens’ administration has pulled about $4 million from the dedicated purse to pay city staff who work on housing-related projects and another $8.8 million to service debt for city-issued housing bonds.

The combined $12.8 million accounts for over 75% of the $17 million the housing fund received as its annual 2% appropriation from the FY 2025 general fund — a hefty share for a fund that totaled $28 million at the start of the fiscal year last July. As of April, the housing trust fund had about $4.7 million in it.

Before February, the city rarely used the fund for payroll and had never tapped it for housing bond payments. Atlanta’s chief financial officer Mohamed Balla said his department took this new approach to confront a budget deficit from FY 2024.

The city has also incurred $175 million in bond debt since FY 2024 for housing initiatives. It approved a $100 million issue of Housing Opportunity Bonds for FY 2024 and then another $75 million Homeless Opportunity Project bond issue in FY 2025 to build 500 rapid rehousing units and 200 permanent supportive housing units.

Red flags

While not a blatant violation of the ordinance that launched the trust, the pivot to funding city staff salaries and housing bonds has raised red flags for housing advocates, who say it undermines the original purpose.

“From the very beginning, this looked too much like a slush fund, and not enough like a housing trust fund,” said William McFarland, the vice-chair of the Atlanta Housing Commission, an independent body the city council created in 2018 to advise on housing matters. The commission helped the city council establish goals for the trust fund in 2021.

“What we had in mind at the time was a more flexible funding stream that would help us get to deeper levels of affordability than what bond funding can do,” said City Councilmember Matt Westmoreland, who authored the enabling legislation in late 2021.

“It’s been used for a great many things over its first three years,” he added. “Part of that is debt service on bonds, which, in and of itself, is not problematic, because those bonds are helping with the construction and preservation of units. The staffing gives me a little more concern.”

Westmoreland said using the housing trust fund this way is within the bounds of the legislation, but he said it should have instituted clearer guardrails.

During public meetings to map out the mission of the housing trust fund, Atlanta Housing Commission chair Andy Schneggenburger said in an interview, “We asked the question, ‘What should a trust fund support?’ The resounding answer was to produce low-income and very-low-income units. That’s where there’s a major gap in our funding sources.”

So when the city council approved a $500,000 donation to a food insecurity nonprofit from the housing trust fund in 2022, Schneggenburger added, “It became obvious that there needed to be some guardrails in terms of how the money was going to be spent.”

City’s response

Balla, Atlanta’s CFO, defended the housing trust’s use for housing bond payments and staff salaries. He said the city initially intended to use $4 million from it to service housing bond debt in FY 2025, but increased that to $8.8 million to cover housing bond costs that should have been charged to the fund in previous years.

On staffing, Balla said the trust is now funding about 40 positions — mostly within the planning department and mayor’s office — which is more than double the city’s dedicated housing staff for previous fiscal years.

Using the housing trust for staffing and housing bond debt service is appropriate, Balla added, since it comes from the city’s general fund and is therefore “not a special-service fund that gets its own money from a unique revenue stream [like a dedicated tax].” What’s more, the housing bond and salary payments directly drive the city’s goal of adding to Atlanta’s affordable housing supply, he said.

Balla cautioned that barring the city from using the housing trust for bond payments would sharply curtail its ability to secure new housing construction financing, such as the $100 million in Housing Opportunity bonds that Invest Atlanta issued at the end of FY 2023. “If we don’t have a way to pay for it, I could not in good conscience let Invest Atlanta go out and borrow $100 million,” Balla said.

Local housing advocates, however, aren’t convinced that the city has no better way of paying down bonds to fund housing. Other big cities — including San Francisco, Denver, and Austin — use dedicated property tax increases to back their housing bonds.

The housing trust fund “should be earmarked for creating new social housing, and there should be a way for the community to be involved in what projects get greenlit,” said local housing advocate Matthew Nursey, the policy director for the Housing Justice League. “There should, at the very least, be some transparency on how much funds are in there and how they’re being used.”

Opaque bookkeeping spurs transparency concerns

The housing trust’s changing role came to light after Atlanta Civic Circle obtained a 4,159-row ledger from the city via an open records request that listed all transactions from the fund’s late 2021 inception until present. That was after asking the city for an accounting of how it spent the funds, similar to the list it provided in 2023.

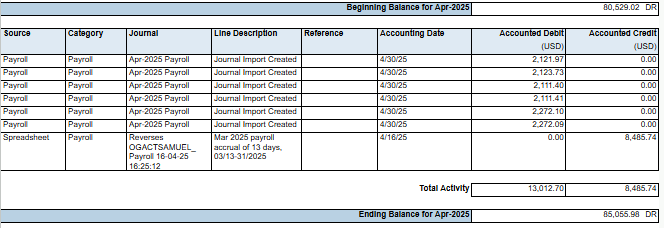

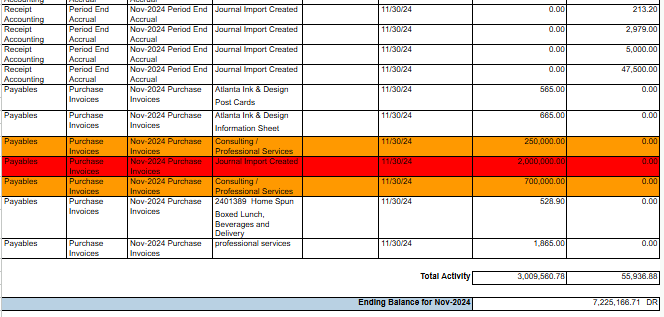

Scattered amid the labyrinth of transactions are hundreds of entries described only as “Journal Import Created” and classified as “Receipt Accounting” or “Payroll” expenses, but without specifying what the payment was for.

Among the more brow-raising findings: more than $5 million in payments for “Consulting/Professional Services” between late September 2023 and April 2025, including two unidentified consulting payments of $1 million each in July and August 2024. The city also paid $4 million in December 2023 to a party identified only as “Supplier #.2401452,” which subsequently returned $2 million. The ledger does not specify what the payment was for.

Balla said he wasn’t sure what those consulting and supplier entries represented, since the ledger is automatically assembled by a computer program — but he promised to find out. “More than likely, the large ones have been legislated,” he said.

Due to the ledger’s disorganized and opaque nature, it’s nearly impossible to tell exactly how much of the housing trust fund was paid out in FY25 to directly build housing or keep people housed. Since its launch, the trust fund has been used for a variety of anti-displacement initiatives, such as grants to legal nonprofits for eviction prevention, a city-administered home repair fund, and property tax subsidies for long-term residents in fast gentrifying neighborhoods.

Reining it in

In response to Atlanta Civic Circle’s findings, Westmoreland said he plans to introduce new legislation in June to narrow how the housing trust fund can be used.

Schneggenburger and McFarland of the Atlanta Housing Commission suggested adding language so that it is used predominantly to develop deeply affordable housing priced for households earning less than 60% of the area median income — or $64,500 for a family of four.

They also suggested restricting it from being used for debt service on housing bonds or for payroll. Westmoreland said he’ll consider all of these ideas.

HouseATL executive director Natallie Keiser emphasized that the housing trust should be used to help Atlanta’s poorest residents to either get or stay housed. “A trust fund provides the unique opportunity to provide grant subsidy — not debt [payments] — to address housing supply needs for people on the lowest end of the economic spectrum,” she said.

But for now, the Dickens administration plans to continue spending a portion of the housing trust fund money for housing bond debt and payroll, in addition to the direct expenditures that keep Atlantans housed.

The city has earmarked $19.5 million, or 2% of the general fund, for the housing trust in FY 2026. Of that, Balla said, the city will use $5.5 million to cover a portion of the $14.5 million in annual debt service for the Housing Opportunity and Homeless Opportunity Project bonds. It also plans to use $1 million for payroll, out of $5 million total for “personnel costs related to affordable housing efforts,” he said.

This story is part of #ATLBudget, a civic engagement project in collaboration with the Center for Civic Innovation and other organizations. Together, we’re breaking down Atlanta’s budget process to show where your tax dollars go — and how you can help shape the city’s priorities. Follow #ATLBudget on Instagram and Bluesky for updates.

Atlanta and Mayor Dickinson is where corruption is the norm. Now, I see why the Mayor and City Council got rid of the Real OIG. Now Atlanta has an OIG in name only.

It’s Mayor Dickens or Mayor Dickhead if you like.

They should call Mayor Dickens Tricky Dick or puppet boy. Whose pulling his strings.

Where is that ethical and effective government? Well, the government is full of Dickens cronies as department heads. You know the usual “family, friends, and fraternity or sorority sisters welfare.”

Where is Ethics? Oh, they are in name only just like the new OIG. I wonder how many individuals that work for the Atlanta City Government have $200,000 salaries?

I wonder how many COA employees are “double-dipping” in those funds?

AHHHHHHH, it all makes sense now!!! The City of Atlanta needed another agency to give the appearance of integrity and ethical government behavior. So, rather than allow the Office of the Inspector General to operate and function as the watchdog that it is purposed to be. The City decided to defang and neuter the Office so that it could be the sister agency to the Ethics Office. What makes the “new” OIG worse is that the office now operates as if the City of Atlanta citizens doesn’t have the common sense to realize that the office is now the Mayor’s new side chick.

P.S. Another thing does Trickey Dickey think he’s the P-Diddy of the South!?!?!?!

It seems to me that Atlanta City Government led by Dickens are as corrupt as they appear. They employ their friends and families even if they are not qualified. They sprinkle a few outsiders in the mix to give them legitimacy. Anytime there may be a questionable legal issue, they get some attorney or retired judge to give it legitimacy. It’s a house of cards. Follow the money.

It seems to me that Atlanta City Government led by Dickens are as corrupt as they appear. They sprinkle a few outsiders in the mix to give them legitimacy. Anytime there may be a questionable legal issue, they get some attorney or retired judge to give it legitimacy. It’s a house of cards. Follow the money.

The grift continues per usual. Who wants to bet that Dickens administration gets investigated for financial malfeasance in five years? This article spells out how corrupt City officials are. Money that is supposed to go to housing for the poor is looted to pay fat salaries, 40 staff members in the Mayor’s office, “donations” to nonprofits that no doubt went somewhere else. It’s outrageous this continues. I hope every one of these grifters gets thrown in prison. The prison that was supposed to be cleaned up with that billion dollar investment that so far has gone nowhere near the Fulton County Jail. Orders from the DOJ mean nothing to Atlanta officials.