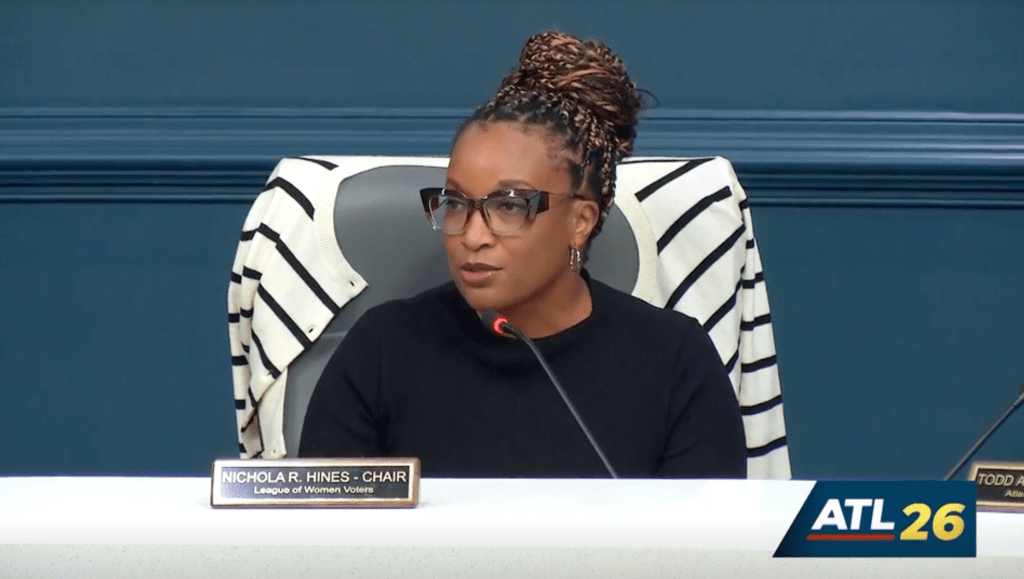

Atlanta’s top corruption watchdog, Inspector General Shannon Manigault, is alarmed. So is Nichola Hines, who chairs the citizen governing board that oversees Manigault’s office and is the League of Women Voters of Atlanta-Fulton County appointee.

That’s because draft legislation introduced during Monday’s Atlanta City Council meeting would substantially gut the independence and investigative powers of the city’s Office of Inspector General (OIG).

“What the legislation does — it is taking Atlanta backwards,” Manigault said.

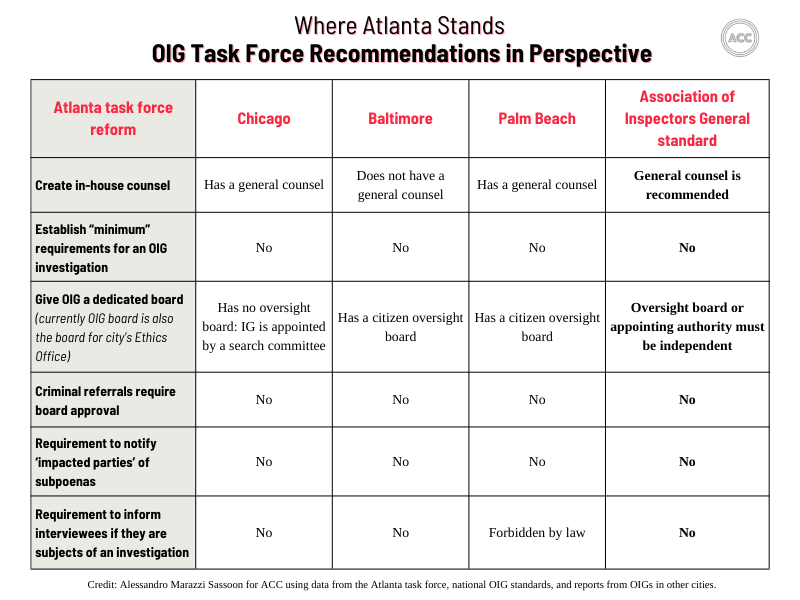

The proposed legislation incorporates recommendations from a task force that the city council convened last fall to review the powers of the OIG and the city’s Ethics Office. If adopted, the changes to the city’s charter would restrict the OIG’s access to city records, limit what the OIG can investigate by setting minimum thresholds of malfeasance to open an investigation, and require subjects under investigation to be notified, which Manigault said would compromise the confidentiality of her office’s investigations.

The changes would also take away the OIG’s discretion to release its investigative findings to the public or to refer any criminal findings to prosecutors – another task force recommendation.

However, the draft legislation submitted to the city council on Jan. 6 goes even further than the task force recommendations. For instance, it would end the independence of the OIG’s nine-member citizen governing board by shifting the power to make board appointments away from the citizens of Atlanta squarely into the hands of the mayor.

What’s more, the bill would strike probing “corruption (illegal acts)” from the OIG’s investigative mandate, which covers “allegations of waste, fraud, abuse and corruption (illegal acts).” That change seems contradictory, said Hines, the OIG board chair, since the Atlanta City Council specifically created the OIG in 2020 in response to a federal corruption investigation into City Hall during former Mayor Kasim Reed’s administration.

“How shortly we forgot the whole reason why the original task force [that drafted the initial OIG legislation] said that we need an Inspector General is because of the corruption that was going on in the city,” Hines said.

City: OIG needs checks

Currently, there’s an existing check on the Atlanta OIG’s broad investigative powers: its lack of enforcement power. While the city’s corruption watchdog currently can open an investigation at will into city departments or employees, it’s up to city leaders to decide what to do with its findings and recommendations.

But some city council members, as well as the Mayor’s Office, believe that the OIG’s investigative powers are still too broad. Atlanta City Councilmember Howard Shook, who authored the draft legislation, was a member of the task force that drafted the controversial reforms, along with fellow Councilmember Marci Collier Overstreet and five prominent local attorneys. Overstreet co-signed Shook’s draft legislation with five other council members: Mary Norwood, Andre Boone, Liliana Bakhtiari, Dustin Hillis and Byron Amos.

Shook did not respond to an emailed request for comment. Emailed requests for comment to Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens and Chief of Staff Odie Donald also were not returned.

The task force — which notably did not consult inspectors generals in peer cities — proposed curtailing the OIGs powers to the point that Manigault has said she would resign if they were adopted in full.

But the draft legislation goes further. “We wanted to make certain that that language about the mission was clear — she’s not the FBI,” Atlanta City Attorney Patrise Perkins-Hooker told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The Jan. 6 bill significantly hobbles the OIG’s ability to conduct investigations that could be ever used as the basis for a criminal probe. One important change is that fact-finding interviews with city employees, which are usually voluntary, must be considered as compelled testimony. That would preclude that information from being used later in a criminal prosecution.

A mayor-dictated board

The proposed legislation also goes beyond the Nov. 6 task force recommendations by stripping the power of citizen groups to select the members of the OIG’s governing board. Instead, citizen groups would merely recommend nominees to the mayor — who would gain the power to actually appoint the board members, subject to approval by the city council.

By contrast, the task force had only recommended making the OIG board a separate board from that which oversees the Atlanta Ethics Office. Both the Ethics Office and the OIG agreed with that change.

The proposed legislation would also cut two of the nine OIG board positions — one that’s jointly nominated by Atlanta’s seven universities and another chosen by the League of Women Voters of Atlanta-Fulton County(currently held by Hines).

“Independence is one of those core tenets … and this just takes a jackhammer to that,” said Manigault. Allowing the mayor to choose the OIG board’s members, she added, would make it little more than a “mayoral department” and “the furthest thing from independence.”

The Atlanta OIG’s current citizen-appointed board is widely regarded as an optimal model for independence in governing an inspector general office. “Even the [Dickens] administration has said that Atlanta is the gold standard when it comes to our board, because we are one of — if not the only – independent board throughout the country,” Hines said.

Investigative powers stripped

Manigault is also opposed to proposed changes in the legislation that would require the OIG to notify city employees that they are under investigation, saying that would undermine an investigation’s confidentiality. Another change would restrict the OIG’s ability to confidentially subpoena city records. Instead, any employees mentioned in the records would have to be notified first and, in some cases, a municipal judge would have to approve the subpoena.

All of that, Manigault said, would slow investigations and allow subjects to cover up potential wrongdoing. “If the provisions that are being proposed were in place last year, for example, we wouldn’t have had the investigations that were completed,” she said.

In the past year, her office uncovered hiring nepotism in Atlanta’s Human Resources Department, which resulted in the firing of the department’s commissioner. The OIG also uncovered corruption in the City Planning Department’s Office of Buildings, where city officials collected bribes to expedite permits, which also resulted in firings.

But city employees who are targeted by an OIG investigation need to know their rights and how the process works, the Mayor’s Office has said. “Employees need to know what their rights are throughout this process and any pending investigations,” Donald, the mayor’s chief of staff, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In response to criticism about the OIG’s methods, Manigault said the office has updated its written protocols to ensure city employees are aware of their rights — for instance, that if the city attorney is present for an interview, that is not the same as a personal attorney.

Since December, Manigault’s office also published a handbook of its protocols to make it more transparent to city employees and the public how the OIG conducts its work.

Communication breakdown

Hines said she felt “blindsided” by the legislation, because the OIG board’s members have had productive conversations with members of Dickens’ administration since the mayor made a surprise appearance at an OIG board meeting before Thanksgiving that was specially called to discuss the task force’s Nov. 6 recommendations.

“I was shocked by the legislation,” the OIG board chair said. “Overall what I felt, and the board felt, was that we were making progress with the administration.”

The mayor’s chief of staff and other senior Dickens administration members subsequently attended the board’s Dec. 14 retreat, Hines said, where they had a “positive” conversation with the Association of Inspectors General board executive, Dave McClintock. His group promulgates best practices for OIG offices nationally.

A negotiation ‘starting point’

The Atlanta City Council gave the proposed legislation a first read on Jan. 6, and then referred it to the finance/executive committee, chaired by Shook, and the committee on council, chaired by Eshé Collins.

Collins, who was just elected as the Post 3 At-Large council member, said she hoped any politicization of the debate over the OIG’s powers would not interfere with doing what’s best for Atlantans. “The political aspect is clouding what the citizens of Atlanta actually want,” she said. “I want this to be a space of objectivity.”

Of the city council’s 15 members, seven signed the proposed legislation to amend the OIG’s charter. That means eight council members plus Atlanta City Council President Doug Shipman have not yet weighed in.

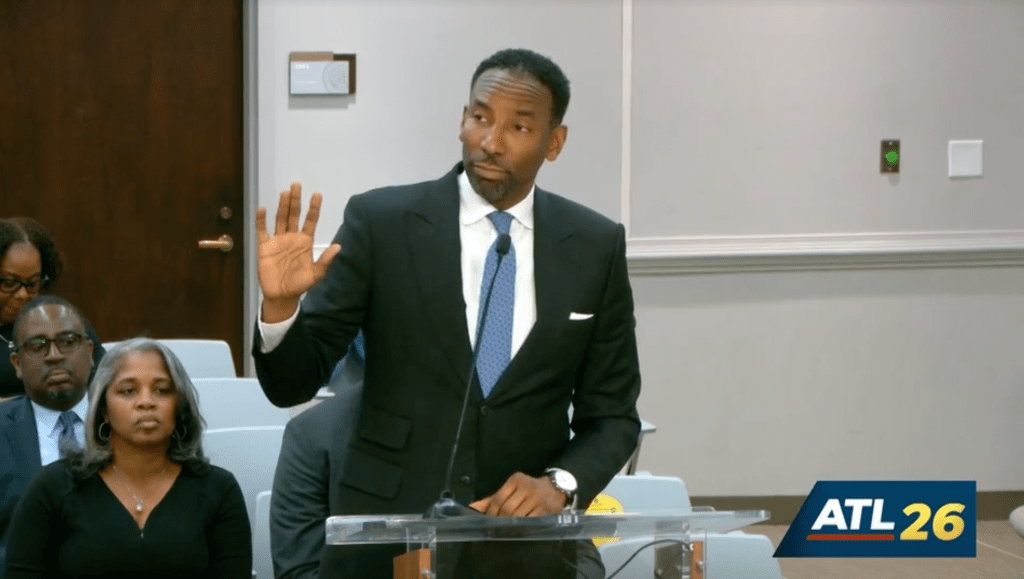

Shipman called the draft legislation “a starting point of a negotiation,” explaining that because the bill amends the city charter, the full city council must vote on it two separate times, so the soonest it could become law is Feb. 3.

Shipman — who cannot vote except in the case of a tie — refrained from commenting on the specifics of the proposal. He did offer some guidance to his colleagues on the council: “As we review this, we should be asking: What problem are we trying to solve here?”

McClintock, of the Association of Inspectors General, said his group still hopes to have a dialogue with Atlanta City Council members and the Dickens administration to address their concerns about the OIG, while also maintaining the city watchdog’s oversight capabilities.

But he did not mince words about what the current proposed legislation would do. “If the intention of this recent bill was to create an Office of Inspector General that is completely incapable of performing its obligations, then Atlanta has a success on their hands,” he said.

Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Nichola Hines was the President of the League of Women Voters Atlanta-Fulton County, and that the League of Women Voters of Georgia not the League of Women Voters Atlanta-Fulton County has nominating authority to the OIG board. Atlanta Civic Circle apologizes for any confusion.