When Trump administration officials abruptly canceled three book events about climate change, the civil rights movement, and homelessness at Atlanta’s Jimmy Carter Presidential Library in February, it spoke volumes about the administration’s plans to address — or not address — pressing social issues, like the nation’s deepening housing crisis.

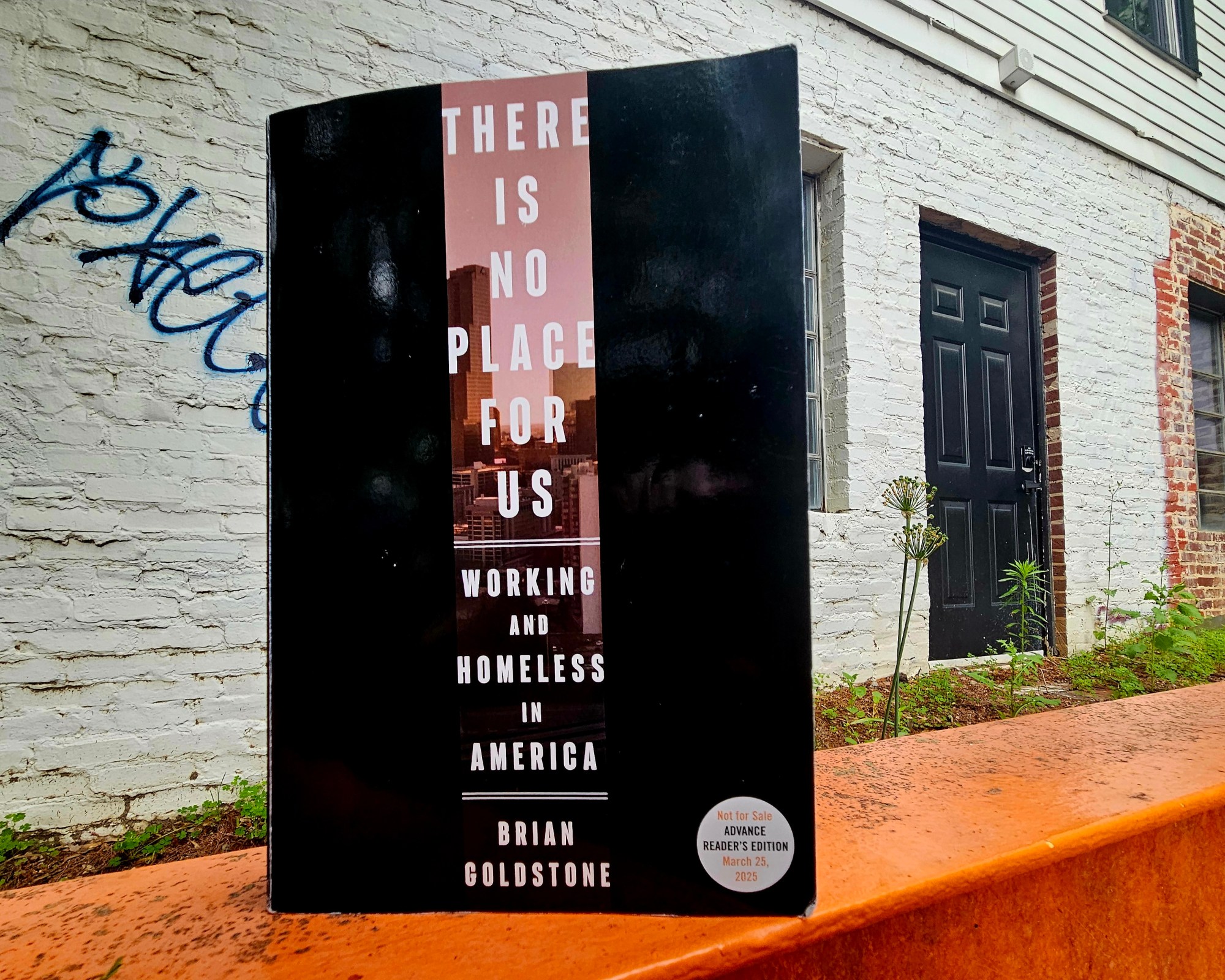

Local journalist Brian Goldstone was one of the affected writers. His new book, “There Is No Place For Us,” offers a sober and resolute portrait of five metro Atlanta families thrust into homelessness, even as their household heads — mostly single mothers — worked their asses off to provide safety and stability for their children.

Goldstone’s book exposes the precarious reality of low-income life in the United States. Across over 300 pages, he documents how the blend of financial strain, family responsibilities, and systemic neglect leaves far too many working families trapped in a cycle of housing insecurity.

Many rely on government safety nets to stay housed, like the federal Housing Choice Voucher program, also known as Section 8, which subsidizes rent for eligible low-income families that can both obtain a voucher and find a landlord willing to take it. That can be a saving grace when income is scarce and life keeps lobbing curveballs. Yet, even as demand soars, America’s public housing subsidies remain chronically underfunded and increasingly inaccessible.

“There Is No Place for Us,” released March 25, proved to be a prescient alarm bell for President Donald Trump’s draft budget, released on May 2, which proposes essentially ending Section 8 and other federal housing voucher programs.

Trump’s proposed $33.6 billion — or 44% — gutting of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) budget would cut HUD’s rental aid programs by $26.7 billion (43%) and send that money to the states as block grants for them to design their own rental assistance programs. It also would impose a two-year limit on rental assistance for “able-bodied” adults. It is up to Congress to either reject or approve the requests.

Who pays the price?

The Trump administration argues the draconian cuts will save the federal government billions. Goldstone’s work makes clear who will really pay the price.

“There Is No Place For Us” rejects the Reagan-era myth of the “welfare queen” or “freeloader.” Goldstone reports on people who are far from idle; they are grinding. They are everyday Americans striving for an American Dream that’s quickly receding further out of reach.

Goldstone spent some five years practically living alongside the heads of the five families he reports on — Maurice and Natalie Taylor, Britt Wilkinson, Kara Thompson, Michelle Simmons, and Celeste Walker. He doggedly documents their efforts to parent their children, find and keep jobs, and secure the one thing that just about every social scientist says is fundamental for a functioning family — housing.

Goldstone’s reporting shows with blinding clarity just how fragile that vital resource can be, especially for people who are a single expensive emergency away from living on the street, in a car, on a family member’s couch, or in an extended-stay motel.

When Celeste Walker’s mentally unwell ex-boyfriend burned down the East Point house she shared with her three children, she never imagined she could still be legally evicted from the charred remains that they’d left behind. Nevertheless, the Prager Group, the Atlanta-based investor that owned the property, had a county sheriff’s deputy post an eviction notice on the door, even noting it was “served to a fire damaged property.”

Although Walker had a job as a warehouse worker and was undergoing treatment for ovarian cancer, she was still branded with a “Scarlet E,” as Goldstone puts it, for missing rent payments on an uninhabitable home.

Likewise, Kara Thompson, an EKG technician with dreams of running her own cleaning business, found herself wedged between her steering wheel and her crumpled-in driver’s side door after getting into an accident, because she fell asleep driving home from the graveyard shift at Grady Memorial Hospital.

Saddled with hefty medical bills and unable to work, Thompson wound up squeezed into family members’ already cramped homes, desperate to find an on-ramp back to stability and normalcy.

Britt Wilkinson, a food service worker, “remembered her elation the day she’d won the [Section 8] voucher lottery and, two years later, her relief at having made it off the waiting list,” Goldstone writes of the single mother who finally secured a Section 8 rental assistance voucher from Atlanta Housing’s limited federal supply.

So when Wilkinson’s landlord told her that her lease would not be renewed because she’d had a houseguest who’d formerly been incarcerated, “she felt only dread.” She was thrown back into the dystopia of finding a landlord who would accept her Section 8 voucher in Atlanta’s high-priced rental housing market.

Goldstone writes: “In early July, Britt requested an extension from her AHA [Atlanta Housing] caseworker and was given an additional thirty days. She prayed for a last-minute miracle. But she didn’t get one. She wasn’t alone: that year, AHA issued 1,674 new housing vouchers; 1,055 expired before they could be used. If Britt hoped to receive another voucher, she would need to start the entire process over again.”

However nightmarish, these stories are not exceptional; they reflect the everyday instability many lower-income renters face as they navigate the rocky terrain of America’s housing affordability crisis.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness this week urged Congress to reject Trump’s budget proposal for FY 2026, saying it would slash almost $40 billion from critical programs that get and keep people housed.

“That is a recipe for disaster,” said the group’s CEO, Ann Oliva, in a May 5 statement. “We know that these programs have been chronically underfunded for decades.”

“This proposal represents the single greatest retreat from the federal government’s responsibility to end homelessness since the passage of the McKinney-Vento Act,” Oliva added. (The 1987 federal law ensures that unhoused children and youth can access free public education, regardless of their housing status.)

The National Low Income Housing Coalition raised similar concerns in its own May 5 statement, with comment from Senate Appropriations Vice Chair Patty Murray (D-WA): “This is a proposal to raise costs and make life harder — and worse — for working people in every part of the country,” the senator said.

Both nonprofits emphasized that Trump’s proposed HUD cuts would cause the nation’s homeless populations to skyrocket. Goldstone’s book lends the crucial human perspective that Congress must recognize before making decisions that will upend the lives of countless Americans.