Five years after the largest police accountability protests in US history, only five of 41 municipal police departments in the five-county metro Atlanta area have any form of civilian oversight.

Those five police departments are the Atlanta Police Department; the Chamblee Police Department in DeKalb County; the Gwinnett County Police Department; and the Kennesaw and Smyrna Police Departments in Cobb County, according to an Atlanta Civic Circle analysis.

All but one are merely advisory committees limited to soliciting community input and offering non-binding recommendations to police leadership. The Atlanta Citizen Review Board, which oversees the Atlanta Police Department, is the only investigative body, and it hasn’t closed a single case since 2020.

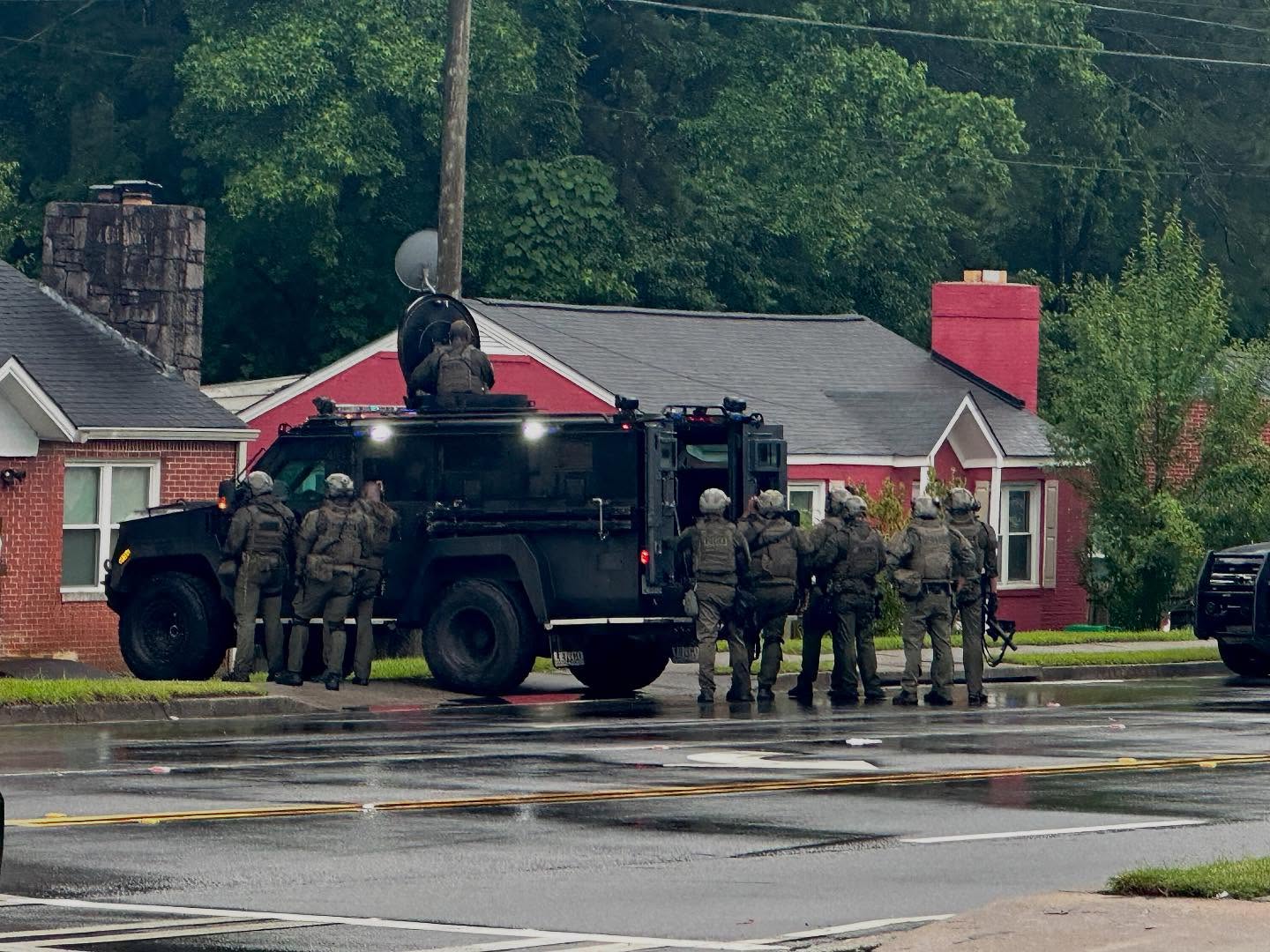

But in DeKalb, a proposal for a citizen board to oversee the DeKalb Police Department is gaining traction. DeKalb has faced public pushback for how police handled a June 14 “No Kings” protest, where officers deployed tear gas on a peaceful crowd and arrested over a dozen people. That included a local journalist, Mario Guevara, who’s been in Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody for over 10 weeks, making him one of the longest-imprisoned journalists in US history.

DeKalb Commissioner Ted Terry initially proposed a citizen review board with investigative powers two years ago. But former police chief Mirtha Ramos objected, warning it would kill morale and worsen staff shortages. Lacking the votes, Terry pivoted to the weaker advisory model now up for consideration by the county commission.

Terry calls it a starting point. “Despite having the largest protests we’ve seen in American history, after George Floyd was murdered, we still have hardly done anything that is concrete in terms of reforms,” he said.

“Something is better than nothing,” he added. DeKalb has citizen advisory boards for other areas of county government, Terry pointed out, so why not for the police department, especially since it has the largest budget?

The DeKalb Police Department is one of the largest forces in metro Atlanta, with over 680 officers and civilian employees. At $185 million, its budget accounted for just over 10% of the county’s general fund in FY 2025.

“If taxpayers want to have full accountability and transparency of how their money is being spent,” Terry said, “let’s start with the one that gets the most money.”

Terry is proposing a year-round, full-time board made up of nine citizens appointed by the DeKalb CEO and the county’s seven commissioners. It would meet regularly with police leadership, share community concerns, and give non-binding feedback to county commissioners. However, board members would have no power to investigate misconduct, nor discipline officers. While they could request crime data and summaries of internal affairs investigations, they would not be able to compel disclosure.

Now it’s up to the six other commissioners to vote on Terry’s resolution, which calls on DeKalb CEO Lorraine Cochran-Johnson to establish the citizen advisory board. The proposal has gained a powerful backer: the DeKalb Fraternal Order of Police, which endorsed it earlier in August. Terry and other supporters see the citizen advisory board as a tool to boost police transparency, but critics see only symbolic reform.

These police oversight bodies merely provide “the illusion of accountability,” said Georgia NAACP president Gerald Griggs. Instead, he thinks the solution is to prosecute police officers who harm citizens. As a civil rights lawyer, Griggs has sued numerous metro-Atlanta police departments over claims of excessive use of force, including wrongful death cases.

So the question for DeKalb — and the public — is not just whether to create a civilian oversight body for policing, but whether these boards actually accomplish anything at all.

A cautionary tale: Atlanta’s Citizens Review Board

The fatal police shooting of 92-year-old Kathryn Johnston during a botched, no-knock drug raid by the Atlanta Police Department (APD) prompted Atlanta to create a 15-member Citizen Review Board in 2007. Three officers received federal prison terms of from five to 10 years for Johnson’s killing, and in 2010, the city paid her family a $4.9 million settlement.

The new civilian oversight board was supposed to be a check on the city’s law enforcement officers, with the power to investigate officer misconduct and excessive force complaints and then recommend discipline.

But between 2008 and 2012, two successive Atlanta police chiefs rejected every disciplinary recommendation the board made, prompting its first director, Cris Beamud, to resign in frustration. The board also struggled with the narrow scope of eligible complaints, cooperation from officers, and frequent board vacancies.

The Atlanta City Council expanded the Citizen Review Board’s powers in 2016 after national protests over the police killing Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri — and again in 2020 after the police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis and then Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta.

That allowed the oversight board to investigate complaints about police discrimination and abuse of authority. Yet the, Atlanta Journal-Constution reported in January that it did not open a single investigation into 46 deadly force cases, including four deaths in police custody, between 2020 and 2024.

The review board and the APD inked a new agreement last month that is meant to increase transparency and trust. Notably, the APD must notify the review board within 24 hours of any officer-involved shootings. In turn, the board must notify the mayor and city council of its decisions on each police deadly force case it investigates.

But skepticism remains. Since the Atlanta review board’s creation in 2007, there’s little indication that Atlanta police’s shootings of civilians have decreased. APD officers killed 38 civilians between 2013 and 2024, with one to eight deaths annually, according to data from Mapping Police Violence. Some of the deadliest years came after 2020. What’s more, the APD is still costing the city of Atlanta millions annually to settle lawsuits. The Atlanta Community Press Collectivereported last month that the city paid out $16 million in settlements for APD-related incidents in fiscal years 2024 and 2025. Of that, $13 million covered alleged excessive force and constitutional rights violations, including at least four officer-related deaths.

Police oversight models: advisory, review, and investigative

There are three basic models for civilian oversight of policing:

Advisory boards, like the DeKalb proposal, are the least powerful. They meet with police, solicit community input, and offer non-binding recommendations.

Review boards receive completed internal affairs files for police discipline and use of force cases, then decide whether to agree with the police department’s findings. Their authority ranges from overriding an internal affairs report to simply issuing a public statement of disagreement.

Investigative boards, like the Atlanta Citizen Review Board, can initiate their own cases, subpoena witnesses, and issue discipline recommendations.

Can oversight boards work – or is the model broken?

For Griggs, the Georgia NAACP head and civil rights attorney, the Atlanta Citizen Review Board’s record proves the entire police oversight model is broken.

“It just shows that there’s a lack of will to actually do the hard work of police accountability,” Griggs said. “I’ve handled at least ten cases where they [the review board] should have opened an investigation – from Maggie Thomas to Rayshard Brooks to Jimmy Atchison and Deacon [Johnny] Hollman.”

The city of Atlanta paid $3.8 million to the family of Hollman, 68, who was tasered and killed by an APD officer in 2023 during a routine traffic accident investigation.

Griggs believes true accountability will only come from the courts. “We’re well past citizens holding the police accountable for anything,” he said. Some officers “need to go to prison,” he added. “Until that happens, the violations will continue.”

Instead of civilian review boards, Griggs thinks a special prosecutor should be appointed metro-wide “to investigate these cases and charge officers who violate public trust.” That would be up to the Georgia Prosecuting Attorney’s Council.

It’s rare for police officers to be criminally prosecuted for excessive use of force, even if they kill people, due to the federal doctrine of qualified immunity. However police departments can still be liable for civil lawsuits.

Tiffany Roberts, the Southern Center for Human Rights’ policy director, has a different take. She thinks civilian oversight boards can be useful — if designed properly.

She pointed to the Atlanta Citizen Review Board’s underused power to conduct “pattern and practice” investigations. For example, if data shows an officer is making “disorderly conduct” arrests far more than colleagues, it could reveal bias, profiling, or some other abuse of power.

Even without disciplinary power, civilian oversight boards can expose these types of patterns and inform criminal defense attorneys, community groups, and policymakers, Roberts said.

But to do that, they must have guaranteed access to policing records, independent from police control, Roberts emphasized. “If there is no ability to independently investigate and access data, don’t call it civilian oversight,” she said. “Call it an advisory panel.”

The police perspective

Even though the DeKalb police union has endorsed Terry’s proposal for a civilian advisory board, its president, Bob Hillis, has his own concerns. “Too often, these boards are filled with anti-police ideologues who use their authority as a political cudgel,” Hillis told Atlanta Civic Circle.

He also thinks citizen boards are unqualified to scrutinize police activity. “Regular citizens can be called upon to make important decisions about a profession about which they have little or no knowledge or experience,” Hillis cautioned.

Hillis offered some recommendations for the proposed advisory board: FIrst, ensure it is full time. Next, train the members on police use of force, deescalation, and qualified immunity protocols.

The board members also should have to do ride-alongs with police. “They need exposure to the unique environment about which they will advise,” Hillis said.

Taking the first step

Terry’s longer-term vision is “civilian-led policing,” where trained community members would be more directly involved in setting police policy. They could also evaluate — or even help hire — the police chief. That’s not a new idea. Congress created the US Department of Justice’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services in 1994 to provide grants and training for community-based policing.

For now, he said, a citizen advisory board would at least create a public forum for the community’s policing concerns – an advance over the two minutes allotted to citizens for public comment during county commission meetings.

But Griggs believes that Terry may be wasting his time. “We don’t need more task forces or review boards. We need prosecutors to do their jobs and send [police officer] violators to prison,” the lawyer said.

Griggs offered a more ominous warning. “If the city of Atlanta and other jurisdictions don’t get their act together, they are one viral video away from being right back to the summer of 2020.”

Are you a DeKalb resident who wants to express your views on a citizen advisory board for the DeKalb Police Department? Email or call your county commissioners here.

Bella Ying is a freshman at Lovett, and is interested in pursuing a journalism degree upon graduating from high school. She was a 2025 Atlanta Civic Circle summer intern.