A special task force that Atlanta City Council convened this fall has recommended sharply curtailing the investigative powers of the city’s Office of Inspector General (OIG).

However, the task force apparently made its recommendations without consulting any other cities’ inspectors general on best practices, raising concerns about their input. Several big-city inspectors general contacted by Atlanta Civic Circle warned that these changes could compromise the Atlanta OIG’s investigative effectiveness.

The city council established Atlanta’s independent watchdog office four years ago to combat corruption, following a federal investigation into City Hall during former Mayor Kasim Reed’s administration that led to the imprisonment of several top city officials.

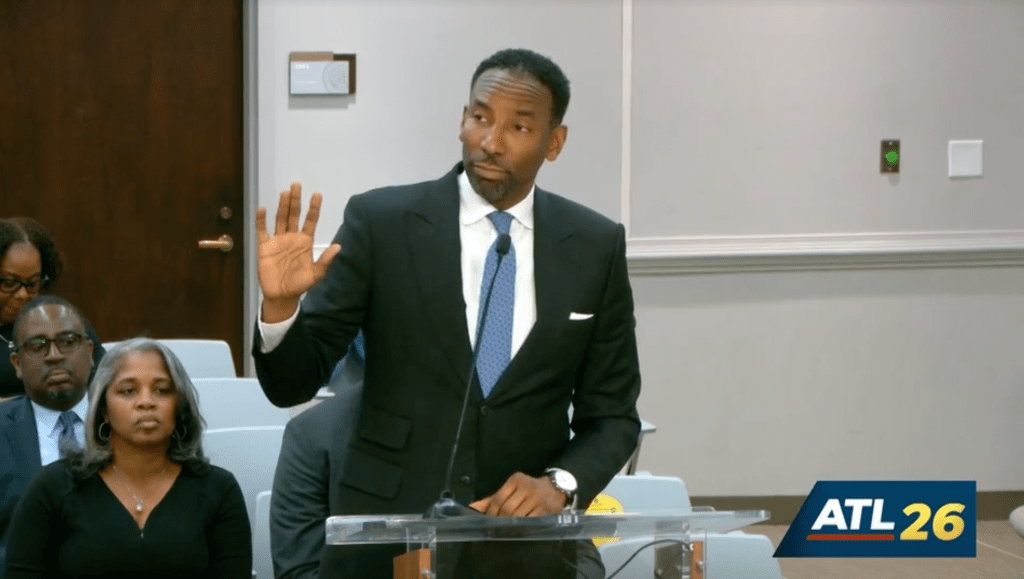

Earlier this year Atlanta’s Inspector General Shannon Manigault raised concerns to the city council of obstruction to her office’s oversight work. Some city council members, officials and Mayor Andre Dickens in turn raised questions about the OIG’s investigative conduct, prompting the formation of the task force through council. Made up of local civic leaders, attorneys, and two city council members, the task force was charged with reforming the oversight and powers of the OIG, and ultimately left Manigault’s obstruction concerns unaddressed.

The extensive recommendations that the task force made in a Nov. 6 report to the city council include setting minimum thresholds of malfeasance for the OIG to open investigations, requiring subjects under investigation to be notified — and taking away the OIG’s ability to release investigative findings to the public or refer any criminal findings to prosecutors.

Those are in addition to an important existing check on the Atlanta OIG’s broad investigative powers: its lack of enforcement power. While the city’s corruption watchdog can open an investigation at will into city departments or employees, it’s up to city leaders to decide what to do with its findings and recommendations.

The task force chair, Leah Ward Sears, a law partner at Smith Gambrell & Russell and former Georgia Supreme Court Justice, declined to comment on the task force’s deliberative process, but she said in an email that task force members did contact other OIGs.

The task force heard presentations from Atlanta Inspector General Manigault, as well as members of the city’s OIG governing board. Meeting minutes also show that City Attorney Patrise Perkins-Hooker received a written submission from Georgia Inspector General Nigel Lange, but task force materials do not include the document. Perkins-Hooker said that was an oversight and the document would be added.

But the task force’s online record of its proceedings does not include input from any other cities’ OIGs on best practices.

Limited input raises concerns

Nichola Hines, chair of the OIG’s citizen governing board, criticized the task force’s lack of consultation from subject-matter experts at a board meeting before Thanksgiving. “The subject experts were not in the room,” she said.

The Association of Inspectors General (AIG) also expressed concerns about the task force’s process after it declined a teleconference with an AIG representative who wasn’t able to travel to Atlanta for an in-person presentation. The group, which promulgates best practices for OIGs nationally, instead submitted a letter that encouraged the task force to engage with other inspectors general, as well as the public, in crafting its recommendations.

“The AIG has significant concerns about the [task force]’s ability to provide meaningful and well-informed solutions for the OIG and the city of Atlanta because of what appears to be limited input from the public and subject-matter experts and a very compressed timeline to do its work,” said AIG president Will Fletcher’s letter.

The Atlanta City Council officially received the task force’s recommendations in early December, but it hasn’t taken any action yet. Atlanta’s inspector general, Manigault, has threatened to resign in protest if the city council adopts them all as they are.

“I’m not willing to collect a paycheck to do nothing,” she said.

So are the task force’s recommendations out of the norm?

Reactions from other cities’ OIGs

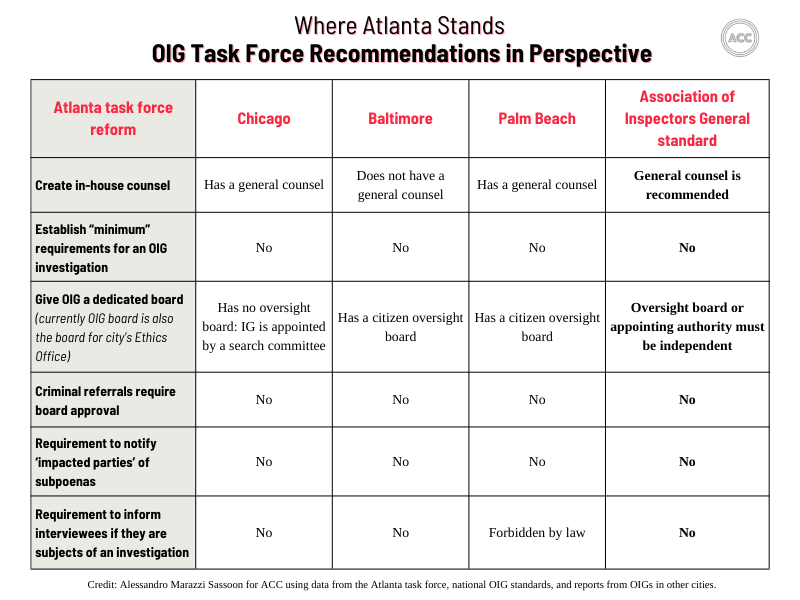

Atlanta Civic Circle contacted inspectors general for Chicago, Baltimore, Richmond, and Palm Beach County, Florida, as well as the Association of Inspectors General, to find out. They strongly supported some of the task force’s proposals, such as providing the Atlanta OIG with an in-house lawyer. However, other recommendations drew sharp criticism.

The inspectors general widely panned proposals to require a minimum threshold for opening investigations, limit the public release of reports, notify subjects of investigations, and provide notice of city records subpoenas to affected parties. These changes would compromise investigative independence and confidentiality, these practitioners said.

“Independence is the hallmark and the animating principle and the lifeblood of effective oversight,” said Chicago Inspector General Deborah Witzburg. For that reason, she added, there shouldn’t be any restrictions on an inspector general’s discretion to initiate investigations into allegations of wrongdoing.

Witzburg and the other inspectors general bristled at the task force’s proposal that there must be a minimum threshold of “gross mismanagement, gross waste of funds, or a substantial violation of law” for the Atlanta OIG to open an investigation.

“Wherever the evidence leads us, that’s the path you take,” said Baltimore Inspector General Isabel Mercedes Cumming.

Cumming called the proposed thresholds for investigations “utterly ridiculous.” Minor complaints can often reveal significant issues, she explained, highlighting her office’s identification of $7 million in fraud and waste last year, much of it originating from seemingly small hotline tips.

Atlanta’s inspector general, Manigault, has similarly expressed strong opposition to the proposed thresholds for investigations. “Atlanta should espouse a zero-tolerance policy for fraud,” her office wrote in a detailed response to the task force recommendations.

The Atlanta OIG cited a recent case where small bribes within the City Planning Department’s Office of Buildings led to a significant investigation and corrective actions. Under the proposed thresholds, such investigations might never occur, her office said.

Investigative confidentiality?

The inspectors general also took issue with the task force’s proposals that the Atlanta OIG must inform any city employees it interviews if they’re the target of an investigation and notify “impacted parties” about any subpoenas of city records.

In the eyes of Manigault and her peers, these changes would undermine the confidentiality of an investigation, giving potential wrongdoers the chance to cover their tracks. They could also put whistleblowers at risk of retaliation, the inspectors general say, since a city employee’s manager might be able to deduce who was in a position to call foul on any underhanded activities. It’s something that has already happened amid an investigation into nepotism earlier this year in Atlanta’s Human Resources Department.

In fact, in Florida, these proposals could run afoul of state law, since active OIG investigations are exempt from disclosure to both the OIG’s city or county leaders and the public. “I have the obligation not to inform either management or the public about an ongoing investigation,” said John Carey, Palm Beach County’s inspector general.

That legal guardrail, Carey said, protects the investigation itself and its subjects — especially if the allegations ultimately prove unfounded.

Oversight versus independence

Atlanta’s OIG currently operates independently, reporting to a citizen board rather than the mayor or city council. To safeguard the OIG’s autonomy, the board cannot dictate how the city corruption watchdog conducts investigations, releases its findings to the public, or refers potential criminal actions to outside prosecutors.

The task force’s recommendations, however, would shift these powers to the OIG’s board. The inspectors general warned that that would undermine the OIG’s operational independence.

“In order to provide objective, rigorous, impactful oversight, offices of inspectors general must be able to initiate and conduct their work without interference or direction from the people they are overseeing,” emphasized Chicago’s Witzburg, who does not report to a board at all. (In Atlanta, the board hires the OIG, while in Chicago, a special committee does.)

Baltimore’s Cumming said Atlanta’s citizen OIG board already provides more oversight than most OIGs receive, since about 80% lack such boards entirely. In Baltimore County, she added, there is an ongoing debate over the county inspector general’s powers, akin to that in Atlanta. However, a blue-ribbon commission established by the county executive actually recommended that its inspector general not even have an oversight board.

That’s because too much oversight can compromise an OIG’s investigations, said Cumming, who also reports to a citizen board. The board should also not include officials who might potentially be investigated, or have a stake in an investigation. “If you have an advisory board, it should be citizen-based,” she added.

Cumming said she’s faced pushback over some of her office’s investigations — especially those touching elected officials. That’s one reason her office’s governing board, which used to include elected officials, was reformed to a citizen-only board.

Cumming added that she’s been accused of playing politics — something Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens has accused Manigault of doing — but that’s not the job.

“It’s always up to the citizens to determine if they want to hire the elected officials that they hire,” she said. “But our job is to shine a light on what is happening and then to move on to our next case.”

Best practices

Palm Beach County’s Carey, like the other inspectors general Atlanta Civic Circle spoke to, said his office follows standards and best practices set by the Association of Inspectors General. The national organization also provides model legislation that localities can use to create an OIG and establish its powers.

Association of Inspectors General spokesperson Dave McClintock said his group aims to serve as a resource for city and county leaders, since it is not uncommon for them to wrangle with their inspectors general over the watchdog office’s powers.

His hope is that municipal leaders view having an OIG as a way to serve the public interest, by building independent oversight into local governance.

“What we have learned, over many years of seeing offices in cities and counties struggle with bringing in truly independent oversight, is that we can best serve as subject-matter experts in helping draft better legislation, helping explain practices that work and that are compliant with the principles and standards for offices of inspector general,” McClintock said.

“But that only works when we’re a part of the conversation,” he added.

Great article, thanks for reaching out to the subject matter experts.

The “written submission from Georgia Inspector General Nigel Lange, but task force materials do not include the document. Perkins-Hooker said that was an oversight and the document would be added.”

Will someone be following up to ensure this happens?